ANNACLONE

Table of Contents and Links to other Family History Pages

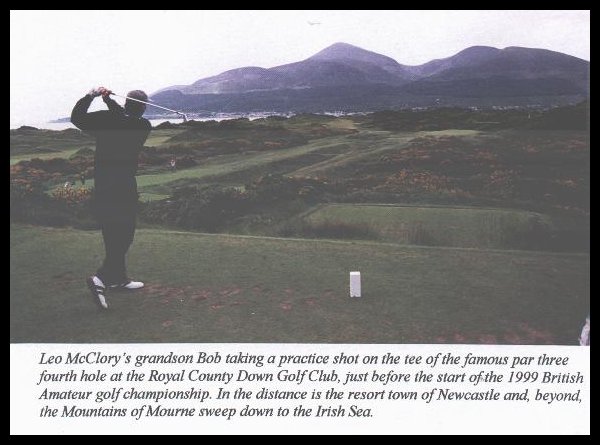

Leo

McClory often told his daughter Betty and his nine other children that his

grandparents were from County Down in the North of Ireland. They had left there

for America on their wedding day, sailing from the town of Newry about the time

of the Great Famine. Long forgotten was the actual year that they had left

Ireland, where in County Down they originated, and what had become of the

McClory ancestors who remained in Ireland.

A

chain of events beginning over two years ago led the 76 year-old Elizabeth

“Betty” (McClory) Kearney, her husband, three of her six children, and a

son-in-law back to the land of her ancestors this past Spring of 1999. These

events include her son Bob’s amateur golf career, and the continuing

development of the Internet.

In

June of 1997, the then 40-year-old Bob Kearney qualified as one of five amateur

golfers to play, among a field of 151 professionals, in the 1997 United States

Open Championship at the Congressional Country Club outside of Washington D.C.

Bob has since gone on to play in three U.S. Amateur Championships.

However, the accomplishment of qualifying as an amateur to play in a U.S. Open

Championship earned Bob an automatic exemption to play in the British Amateur

Championship for the following five years.

Of the future sites selected for the British Amateur, one

would be held in Ireland in 1999 at a course considered among the world’s ten

best. A British Amateur Championship to be played in Ireland would prove too

great an opportunity for Bob to pass up. He decided that he would travel from

his Houston home to Ireland in late May of 1999 to play in the tournament. Many

in his family also decided to accompany him: his sister Joan Winterfield and her

husband Nate from Colorado Springs, his parents from Hamden, Connecticut, and

myself from Seattle.

However,

my siblings and I had forgotten the stories that our mother had long ago passed

on to us from Leo McClory. Until Betty Kearney reminded us, we had not realized

that the golf course, the Royal County Down Golf Club in County Down, Northern

Ireland, was also located in the homeland of our McClory ancestors.

In

the few short weeks before departure to County Down, the writer gathered

existing family information and commissioned ancestral research to be undertaken

in Ireland. Much assistance was provided by Betty Kearney, Charles McClory of

Pittsburgh, Mary McClory of Pittsburgh, Regis McClory of Trowbridge, Illinois,

and Robert McClory of Evanston, Illinois. With little time or background

information, the Ulster Historical Foundation in Belfast agreed to conduct

research in Ireland and to communicate expeditiously by e-mail and fax.

The

information in this report originally unfolded as if solving a detective

mystery. Leo’s daughter, Mary McClory, first provided a 34-page family history

written by hand in 1958 by Leo’s older sister Mary (“the 1950’s

history”). A nephew of Leo, Regis McClory, was located in Trowbridge and found

a grave marker and birth date of the first child born to Leo’s grandparents.

After days of tedious searches, the Ulster Historical Foundation came up with

the first potential lead: an obscure marriage record and birth record from a

small town in central County Down.

However,

with just a few days remaining before our departure, we still lacked a

reasonable secondary confirmation as to the town in County Down where the McClory's

originated. Then, amazingly, a distant relative from the Illinois line,

Robert McClory, was found in Chicago. Robert is a teacher of religious studies

at Northwestern University and a grandson of the youngest of Leo’s six uncles.

Whether good fortune or the luck of the Irish, Robert and his brother Eugene of

Fort Mitchell, Kentucky, had in their possession many of the remaining family

documents from the Illinois branch of our family.

Robert

immediately located and faxed a typed, seven-page history written by Mary

Henneberry, a granddaughter of another of Leo’s

six uncles from the Illinois branch. This history refers to dates as late as

1976 (“the 1970’s history”). It also contained information that provided

the reasonable confirmations as to the location of the McClory ancestral home.

After

our return from Ireland, Robert found and provided what was effectively the

oldest history of all. It was 14-pages of handwritten copies or summaries of

earlier notes. The summary was again written by Mary Henneberry and made

reference to notes originally written as early as 1930 (“the 1930’s

history”).

These

prior family histories are priceless. Reading their many stories makes our

ancestors come to life. As such, no attempt was made to rewrite or to

consolidate them. However, most of the stories pertain to our family’s history

after our ancestors arrived in Pittsburgh. The purpose of this summary is to

address the questions of where in County Down our McClory ancestors originated,

when did they leave, why did they leave, and what became of our ancestors who

stayed in Ireland.

In

the early 1800’s, the Allegheny Mountains were the western frontier of the

United States. The Northwest Territories that would later become Illinois,

Indiana, Michigan and Ohio were rich in timber, minerals, and fertile land for

farming. But to reach them took weeks of bone-jarring travel on rutted turnpike

roads that baked hard every summer and dissolved in a sea of mud each winter. At

that time, the principal gateway to the west was through Pittsburgh and down the

Ohio River.

The

opening of the Eire Canal across upstate New York in 1825 would spur the first

great westward movement of American settlers and provide access to the rich land

and resources west of the Appalachians. The canal also would eventually result

in New York City becoming the preeminent commercial city in the United States,

far surpassing its principal rival at the time, Philadelphia.

To

compete with the Eire Canal, the worried financial leaders of Philadelphia

convinced the Pennsylvania legislature in 1826 to authorize the construction of

a canal from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. In 1834, the Pennsylvania Main Line

Canal was opened for service, reducing travel time from Philadelphia to

Pittsburgh from a minimum of twenty-three days to as little as four days.

A

36-mile link over the Allegheny Mountains between Hollidaysburg and Johnston was

handled by the Allegheny Portage Railroad. Much like today’s single incline

rail on Mt. Washington in downtown Pittsburgh, the portage railroad was equipped

with ten incline planes, five on each side of the mountain. These planes lifted

the canal boats on railroad-type flatcars up and down the ten inclines. As

locomotives at the time did not have the power to pull the cars up the steep

mountains, stationary engines were used at the head of each incline to pull the

cars using an endless system of ropes (wire cables were not introduced until

1847). Locomotives or gravity were used on the more level stretches of the

mountain between the inclines. Canal systems on both sides of the Alleghenies

then connected Johnston to Pittsburgh (utilizing 66 locks to overcome an

elevation change of 1,700 feet), and Hollidaysburg to Philadelphia.

Records

from the Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society indicate that

the state’s Canal Commissioners allowed reduced fares for immigrants who had

recently arrived in Philadelphia and who traveled west on the canal. According

to Ms. Diane Garcia of the Allegheny Portage Railroad National Historic Site in

Gallitzin, Pennsylvania, the regular fare for passage between Philadelphia and

Pittsburgh was $12 with any of the several transportation companies operating on

the Main Line Canal. She also stated that she would not have been surprised if

some people elected to walk up and down the inclines as the sight of huge boats

on an inclined railcar being pulled with ropes up a steep slope would have

likely been frightening and appeared dangerous.

A

costly and amazing engineering feat of its day, the Main Line Canal and

Allegheny Portage Railroad would be shut down in 1857 after only 23 years of

service. It was replaced by the Pennsylvania Railroad which opened the first

rail line into Western Pennsylvania in 1854, linking Pittsburgh to Philadelphia.

Information

from a couple of sources provides a very good indication as to the year that

Leo’s grandparents left Ireland.

According

to all prior family histories and stories, John McClory and Bridget Dewey were

married in County Down and left for America on their wedding day. Their first

child would be a daughter named Mary, who was followed by seven

sons. In the

cemetery at the now demolished Saint Patrick’s Church in Trowbridge, Illinois,

the grave marker for Mary (McClory) Moran indicates that she was born on March

28, 1838.

Both

the 1930’s and the 1970’s histories also provided important and similar

references to the year 1838. The 1930’s history states that “John and

Bridget arrived in Philadelphia, took a canal boat to the Allegheny Mountains,

walked across the mountains, took a train on the other side, and arrived in

Pittsburgh in 1838”. (Clearly, they had traveled on the Main Line Canal and

Allegheny Portage Railroad. Although this sentence in the family history is

remarkably accurate considering that it was probably first written down more

than 50 years after the actual event, a less ambiguous phrasing of this sentence

probably would have been that… “John and Bridget arrived in Philadelphia,

took a canal boat to the Allegheny Mountains, walked up the mountains, took a

train to the other side, walked down the mountains, and arrived in Pittsburgh by

canal boat in 1838.”)

John

and Bridget were also buried at St. Patrick’s cemetery in Trowbridge. Their

grave markers state that John was from County Down and died August 25, 1879 at

age 68, and that Bridget died January 31, 1888 in her 71st year. Accordingly,

John was born about 1811 and Bridget most likely in 1816.

Based

upon these key dates and some additional information outlined below, the likely

circumstances surrounding John and Bridget’s immigration to American begin to

emerge.

John

and Bridget most likely married and left Ireland in 1837, or very close to 1837.

John was about 25 and Bridget about 21. Based upon our longstanding family

stories, they left from the port of Newry. In the History of Newry (p.135) at the Newry main library, it states the

following with respect to the period of the famine in the late 1840’s:

“…Being a port of some significance, Newry

became the centre of emigration for

southern Ulster and northern Leinster. Ships carried thousands from Newry and

Warrenpoint, sometimes directly to America or, more often, to Liverpool, the

major centre of emigration in England.”

County

Down is in “southern Ulster”. Warrenpoint is a smaller port town located a

few miles from Newry on the same inlet from the Irish Sea. John and Bridget may

have sailed directly to Philadelphia. It is also possible that they first left

from either Newry or Warrenpoint by regular steamer service to the large

embarkation hub of Liverpool, England. During the famine years of 1845 through

1848, for example, published sources have reported that 76% of all Irish

immigrants who arrived at the port of New York had first come through Liverpool.

The

U.S. National Archives maintains on microfilm an alphabetical list of passengers

indexed from the passenger lists from all ships arriving in Philadelphia between

1800 and 1906. John and Bridget are not on the list. This is not at all unusual.

The records are known to be far from complete. Only four McClory's are listed for

this entire period, all arriving on the same ship.

The

first steamship to cross the Atlantic, Steamship Sirius of the British and

American Steam Navigation Company, did not make the crossing until April, 1838,

one month after John and Bridget’s first child was born in Pittsburgh. In

1837, John and Bridget would have crossed the Atlantic on a wooden,

schooner-type vessel with sails. Trans-Atlantic sailings in such vessels

generally occurred more frequently, and certainly would have been more

desirable, from spring to mid-fall. Marriage in the late spring of 1837 could

have resulted in a May or June sailing to Philadelphia, arrival in Pittsburgh

sometime in the last half of 1837 or in early 1838, and a first child being born

in Pittsburgh at the end of March in 1838.

An

attempt was also made to find a marriage record for John and Bridget in Ireland.

The Ulster Historical Foundation in Belfast reported that civil registrations of

marriages for Roman Catholics only became obligatory in Ireland in 1864, versus

in 1845 for Protestants. Before 1864, research success is dependent upon

imperfectly maintained church records, which were often lost or destroyed by

fire. The Foundation was unable to locate a marriage record for John and Bridget

in either the Newry parish or three other parishes in Central County Down which

had high concentrations of McClory's in the 1830’s.

John

and Bridget were from County Down. However, the connection with Newry is less

clear, and has likely been somewhat misunderstood.

Newry

was mentioned by Leo McClory in his stories to his children. Newry is also

mentioned in a short letter written by Leo’s sister, Sister Mary Josephine, to

Betty McClory in about the 1960’s, which states that John and Bridget were

born in the town of Newry. Finally, in the 1950’s history written by the older

sister of Leo and Sister Mary Josephine, it states that John and Bridget married

in Newry. However, the older 1930’s history as well as the 1970’s history,

both written by the Illinois branch of the family, does not mention Newry. These

histories state only that John and Bridget came from County Down.

The

likely explanation for these inconsistencies is that references to living or

marrying in Newry probably refer to in the area of Newry.

According

to the History of Newry, between 1820

and the late 1800’s Newry was Ireland’s largest commercial center north of

Dublin. A canal over fifteen miles long had been built from the port of Newry to

Ireland’s largest lake in the interior of the Ulster Province. In this period

prior to railroads, shipping by water vastly dominated all other means of

commerce. Newry’s geographic position as a Port, and the existence of its

inland canal, provided the city access to a vast hinterland and a steady flow of

goods.

Although

the nature of the Irish economy and the English system of land-leasing left most

Irish impoverished, Newry was relatively prosperous. In 1842, novelist William

Makepeace Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair

and Barry Lyndon, wrote of Newry in

The Irish Sketch Book, 1842:

“Steamers to Liverpool and Glasgow sail

continually. There are mills, foundries and manufactories….and the town, of

13,000 inhabitants, is the busiest and most thriving that I have yet seen in

Ireland.”

Today,

Belfast is the largest commercial center north of Dublin. However, Belfast did

not surpass Newry until 50 years after John and Bridget left Ireland.

The

information presented in the next sections indicates that John and Bridget came

from a town about fifteen miles northeast of Newry in central County Down. John

and Bridget probably sailed from Newry, and may have possibly married in Newry.

However, immigrants living in the U.S. and originating from anywhere in central

County Down would have often, for convenience, identified themselves as coming

the largest recognizable city close to where they lived, which would have been

Newry.

A

good analogy to this misunderstanding is the lifelong presumption on the part of

myself, my mother and probably many other family members that since our

ancestors left Ireland ‘at the time of’ the Irish Famine, that their leaving

was presumably associated with the catastrophe of the Great Famine. This

assumption has clearly been wrong. The Great Famine lasted from 1845 through

1848. John and Bridget left Ireland at least eight years prior to the start of

the famine. From the standpoint of a parent in the 1900’s telling a story to

their children, the year 1837 could certainly be considered ‘about the time

of’ the famine. Likewise, the McClory homeland was likely not in Newry, but in

the Newry area.

O’Mary

this London’s a wonderful sight

with the people here working by day and by night.

They

don’t sow potatoes nor barley nor wheat

but there’s gangs of them digging for gold in the streets.

At

least when I asked them that’s what I was told

so I just took a hand at this digging for gold

but for all that was found there I might as well be

where the Mountains of Mourne sweep down to the sea.

Percy French

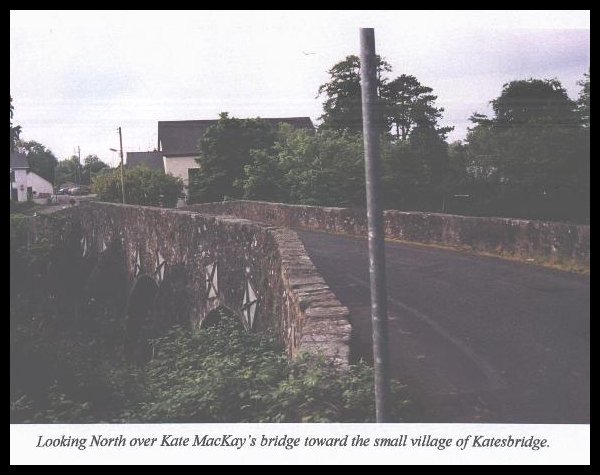

The

River Bann has it origin high in County Down’s fabled Mountains of Mourne, a

mere six miles from the Irish Sea to the east. But instead of flowing the short

distance east, the River Bann winds its way north for almost eighty miles to

cross all of Northern Ireland, finally emptying into the Atlantic Ocean at the

far northernmost tip of Ireland.

As the River Bann completes its short descent to the base

of the Mountains of Mourne, it begins to meander through the beautiful, rolling

green farmlands of Ireland. It passes an endless hodgepodge of small farms with

fields enclosed by ancient stone walls and earthen hedgerows. It flows past

numerous ‘magical’ trees and thickets of bushes where the local farmers have

for centuries claimed that the fairies live, and which they dare not disturb. It

flows through a land where grass grows so lush and hearty that the vast armies

of sheep and cow spend long hours merely sitting idle in the fields instead of

searching for food.

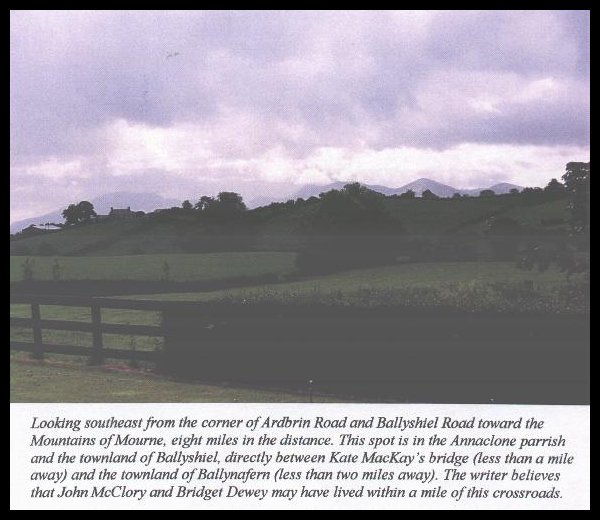

Less than ten miles from the foot of the Mountains of

Mourne the River Bann reaches the heart of the small village of Katesbridge,

crossing under a centuries old stone bridge built with graceful arches and

subtle curves. The river then continues beyond to form the northeasterly

boundary of the adjacent town of Annaclone. With the Mountains of Mourne looming

off in the distance, the story of the McClory homeland brings us to this place.

A few weeks before our journey to County

Down, Leo

McClory’s daughter, Mary McClory of Pittsburgh, sent to me a copy of the

1950’s history written by Leo’s sister. This was the beginning of the

research. For purposes of determining where in County Down the McClory's originated, this family history provided only two small pieces of information:

it stated that John and Bridget McClory married in Newry sometime in the

1830’s and came to America the same day, and it referred to a sister of

John’s whose married name was Nancy Kearney (no known relation to the writer).

No other details were given.

A

few days after receipt of the 1950’s history, I contacted Regis McClory, a

nephew of Leo, who lives near St. Patrick’s cemetery in Trowbridge, Illinois.

Eager to assist, Regis made two trips to the cemetery in search of a grave

marker for a person Regis had never heard of. On his second trip, he found the

marker for Mary Moran indicating that she was born on March 28, 1838. As Mary

(McClory) Moran was the first child born to John and Bridget, and as John and

Bridget by all accounts left County Down on their wedding day, it could be

assumed that John and Bridget probably left County Down in 1837, or possibly

1836.

With

only these few slim details, the next step was to contact the Ulster Historical

Foundation in Belfast, who agreed to undertake some ancestral research in County

Down.

In

Ireland, family surnames have been indexed for all parishes based upon a church

tithe survey listing farmers in about 1830, and a valuation survey of all

properties conducted about 1864. These were checked for all parishes in County

Down for the surnames McClory and Dewey. The McClory name was prevalent in the

surveys, whereas the Dewey name was not. The 1864 property survey listed 54

McClory properties of which 42 were concentrated in three adjoining parishes in

central County Down: the Adhaderg parish with 15, the Annaclone parish with 14,

and the Drumballyroney parish with 13. The Dewey name only appeared once in the

County. Several variations on the Dewey name were checked, such as Dowey and

Douie, but were also not very common. However, to find such a large

concentration of McClory's in such a small area of County Down was an unexpected

and exciting development.

The

Foundation had also indexed all surviving pre-1900 registers of baptisms,

marriages and burials for the Roman Catholic parishes in County Down. Civil

registrations of births, deaths, and marriages only became obligatory for Roman

Catholics in Ireland in 1864. Prior to 1864, records are incomplete. It was in

these records that the first potentially significant connection was discovered.

Although

no marriage record for John and Bridget could be found, a marriage record was

found for a John Kearney and an Anne McClory dated 1843. Based upon the

Foundation’s experience, they felt that it was most likely the marriage record

for the sister of John McClory. At that time, according to the Foundation, the

name Nancy was always used as a nickname for the formal name of Anne. It was

sometime later that the name Nancy evolved into a formal name in and of itself.

The

marriage record indicated that both Anne McClory and John Kearney were from a

town named Anaghlone (old English for the modern day Annaclone).

At

this point, a second potential connection followed relatively quickly. The next

day the Foundation found a birth record in the Annaclone parish dated March 6,

1846 indicating that a son Bernard had been born to John Kearney and Anne

McClory. This was followed by more than a week of continuous searches which

failed to turn up anything.

To

reasonably establish that Annaclone was John and Bridget’s likely place of

origin in County Down, more direct evidence was needed. With five days remaining

before our departure to Ireland, my last hope was to try and find a distant

relative from the Illinois branch who may have some additional information.

After leaving a telephone message in Chicago for Robert McClory, we first talked

three days later. Robert and his wife had visited County Down the prior year and

had spent some time driving around looking for McClory's without be able to find

any. Robert said that he had received some family history information originally

in the possession of another relative, Mary Henneberry, who had died in 1992.

That day, Robert faxed a copy of the 1970’s history written by Mary Henneberry.

To my complete astonishment, this history indicated that:

·

Nancy’s

husband’s name was John.

·

Nancy’s

first child was a son named Bernard.

·

John

McClory was the first of seven children, and Nancy (“Anne”) was the fifth

child. (This was important. If John married about 1837 at the age of about 25,

it is reasonable that a younger sister Nancy would have married about 1843.)

This provided reasonable confirmation that the marriage

and birth records found in Ireland were, in fact, those of John McClory’s

younger sister Nancy.

Further,

the 1970’s history provided some vague information which could potentially

indicate John and Bridget’s place of origin. The history states that Bridget

Dewey’s sister Molly was born in 1813 and…

“Married at about age 40 to Charlie Peterson in

Ireland and lived about 20 miles from Belfast, near Kate MacKay’s Bridge and

Belle Shote (?) and Belle Negrehin

(?)”

The

question marks in the text of the history obviously indicate that whoever

originally wrote the names of these places had no idea how to spell them.

While

studying a map of Ireland, I was suddenly startled to notice a small village

named Katesbridge. It was located right next to Annaclone. The River Bann

divided the two small towns.

Another

intriguing development quickly followed. The names of the old Irish townlands

are rarely used any longer, and do not appear on modern maps. Many of the

ancient townlands contain the word “bally” within the overall name. The

names “Belle Shote and “Belle Negrehin” contained in the family history

would likely be the names of old townlands located somewhere near the major

local landmark for that area, Kate MacKay’s Bridge. I then remembered that The

Ulster Historical Foundation had earlier faxed a small old historical map of the

Annaclone parish. It so happened that the map also showed most of the old

townlands in the parish. Two of the townlands within Annaclone, and in close

proximity to each other, were named Ballyshiel and Ballynafern. Ballyshiel was

also immediately along the border with the adjacent village of Katesbridge.

We

left for Ireland two days later.

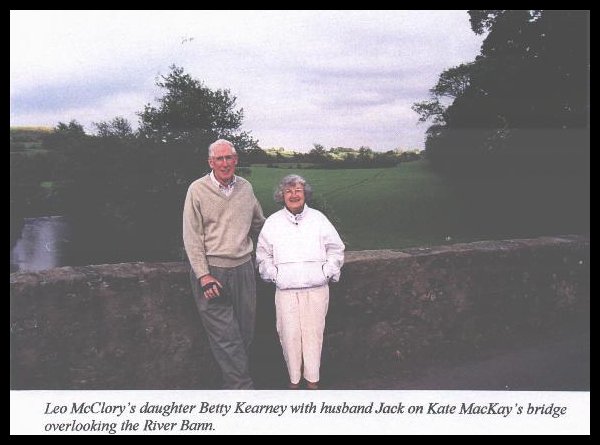

On

a rainy Saturday morning, May 29, 1999, possibly the first descendents of John

and Bridget in 162 years returned to Annaclone just as a special Saturday mass

was starting at the beautiful little parish church. Betty (McClory) Kearney met

her first Irish McClory descendent, Kathleen Farrell (whose mother was a

McClory), during the mass celebrated that morning by the Annaclone parish’s

priest, Father Frank Kearney.

That’s

right. We had journeyed to Annaclone with the former Betty McClory and her

husband John Kearney based upon a marriage record indicating that an Anne

McClory had married a John Kearney there in 1843, and immediately upon arrival

at our first stop at the Annaclone church, we meet a McClory descendent at a

mass said by Father Kearney. Either Irish eyes were smiling, or some local

fairies were up to some mischief, or the spirits of our McClory ancestors were

happy to see us.

After

mass we had a long and splendid conversation with Kathleen Farrell and Father

Kearney. Although Kathleen was a grandmother many times over and had lived here

all her life, neither one knew if Katesbridge and Kate MacKay’s Bridge were

one and the same. At this point, we were extremely anxious to answer this

question as it would then definitely link our written family histories to this

place. They politely suggested that we might look up a 75 year-old man living

near Katesbridge named John Hugh McGinnis who would know about local history. We

politely thanked them, but had little intention of bothering anyone.

But

the spirits of our McClory ancestors refused to remain still. As we drove away

from the church an annoying rattling sound could be heard on the car roof. We

drove a mile to an intersection and pulled over to find that the roof antenna

had mysteriously come loose from its clip. Before we could drive off a very old

man seemed to come from nowhere and was hurrying towards the car. Dressed in an

old heavy wool suit with wool cap and tie, he asked for a lift down the road. I

looked at the four of us in our compact car, looked at him, and told him to

“jump in”. Before he could, out of thin air, a mile from the church we left

not minutes before, Father Kearney walked up behind the very old looking man.

“This is who I told you about. This is John McGinnis.” said Father Kearney.

I immediately asked John if Katesbridge and Kate MacKay’s Bridge were one and

the same. The question had startled him. After a moment of searching thought, he

answered “the old story goes that Katie MacKay lived in a cottage next to the

bridge and made tea every day for the workers who built it”. Needless to say,

this was confirmation enough for us. At that moment, we knew we had returned.

All

of the local sources who we later talked to thought that the names “Belle

Shote” and “Belle Negrehin” contained in the 1970’s history must refer

to Ballyshiel and Ballynafern. They could not see any other logical explanation.

There were no other places with similar names anywhere near Kate MacKay’s

Bridge or in the entire area.

It is also interesting to note that Bridget’s sister

Molly would have married about 1853, which was about 16 years after Bridget left

for America. Obviously, Bridget received communications from or about her sister

for many years after she left Ireland. There is no indication that Bridget could

read or write. It is somewhat remarkable for the names of these places to have

even survived for so long after 1837. They probably were not written down for

the first time until the late 1800’s or early 1900’s. For John or Bridget to

have such knowledge of the area around Kate MacKay’s Bridge so many decades

after leaving County Down may be a further indication that this is where they

likely originated.

In

summary, no records with respect to John or Bridget have yet been found in

County Down. However, a marriage and birth record found in Ireland with respect

to John’s younger sister both indicate that she was from Annaclone, and

completely separate information from family sources in the U.S. indicate that a

sister of Bridget married and lived in or very close to Annaclone as well.

This

is the basic information that led six of us on our journey to Annaclone. For

those of us who made the trip, studied the research results, talked to the local

residents, and spent hours in cemeteries reading McClory gravestones, there is

reasonable certainty on our part that Annaclone is where John and Bridget

originated. At the very least, this

summary may provide the background information that may inspire other McClory

family researchers on both sides of the Atlantic to continue to move the

research forward.

In

the parish of Annaclone, two miles south of the townland of Ballynafern, is the

small townland of Imdel. It was in Imdel that Eleanor (“Alice”) McClory’s

first of ten children was born on March 17, 1777. Alice had married Hugh Brunty

the previous year. In 1802, their first born, Patrick, would leave his humble

origins in County Down far behind to enter St. John’s College in Cambridge,

England.

Driven

by ambition, Patrick changed his name to the more impressive sounding Bronte. He

was ordained as a clergyman and became a published author of poetry and fiction.

Three of his six children, Charlotte, Emily and Anne Bronte, would go on to

write some of the world’s greatest literature and poetry, including the

classics Wuthering Heights and Jane

Eyre.

John

and Bridget McClory married in County Down in or close to 1837. Also in County

Down, and also in 1837, Larry Boise (or Boyce?) would marry Mary Morgan. The

Boise’s would go on to have four children and would be living in Ohio when

Mary Boise died after being stepped on by a cow. According to the family

histories, their daughter Lizzie, born in 1857, would go to live with John and

Bridget’s family, also living in Ohio at that time. Lizzie would later live

with the McClory's in Illinois as well, possibly moving there with them in 1864.

In 1877, she would marry one of the seven McClory sons, and would become the

mother of Leo McClory.

Just

as Patrick (McClory) Brunty would leave County Down in 1802, and John and

Bridget McClory would leave in 1837, and Lizzie (Boise) McClory’s parents

leave in or after 1837, many other McClory's would leave their ancestral homeland

as part of a mass migration over a relatively short period.

Much

has been written about this migration in general. Sometimes the reasons for

emigrating appear obvious. John’s sister Nancy McClory married John Kearney in

1843, the first of the several great potato crop failures occurred in 1845,

their first child was born in 1846, and sometime after that Nancy’s family

arrived in Pittsburgh where John’s family was living. Sometimes the reasons

appear less obvious. The following are a few points which may shed some light on

the particular situation of the McClory's of central County Down prior to the

great famine.

In

October of 1834 and January of 1837, the very last years that John and Bridget

lived in County Down, England’s Royal Engineers happened to have undertaken

detailed ordinance surveys of the parish of Annaclone. These surveys provide an

exceptionally unique insight into life in Annaclone at that time, as well as

possible clues to the McClory migration. According to the surveys of 1834 and

1837:

“Towns…

There are neither towns nor villages in this parish (Annaclone)…”

“Public

Buildings…The only building of any note in the parish is the Established

(Protestant) Church, situated in…Ardbrin…The Roman Catholic Chapel…in…Tullintanvally…In

the same townland…is the Seceding (Presbyterian) meeting house…The

Presbyterian meeting house in Ballynanny…”

“There

are no resident gentlemen…but there are a few most comfortable

farmhouses…Mr. Brown’s…Mr. McKibbin’s…and Mr. William Hillis’s…are

each 2-storeys high, which is rather an uncommon thing in this part of the

country.”

“Locality…

comprises 12 townlands, containing an area of 6,544 and a quarter acres. With

the exception of about 196 acres of exhausted turf bogs scattered over the

parish, it is all under tillage so it cannot be said to be in a good state of

cultivation. The chief and best manure, lime, lies at such a distance, namely…

12 miles, that its great expense retards cultivation and improvement.” (The

Royal Engineers emphasize this point by presenting detailed calculations with

respect to the unprofitable economics to move lime to Annaclone.)

“Bogs…

There are very few bogs in this parish and any that remain are mostly exhausted.

The largest is Monteith bog…which together with a small lake in the centre

covers about 60 acres…McClory’s bog in the townland of Tullintanvally covers

about 12 acres…It is exhausted, the greater portion converted into pasture and

meadow…”

“Habits

of the People… The cottages are generally of stone and thatched, with 3 and 4

rooms on the ground floor. Food: potatoes, meal, milk and sometimes bacon. The

fuel is turf mostly, got in the Lacken bog in the adjoining parish of

Drumballyroney.”

“Farming…

The farms vary in size: very few exceed 30 or 40 acres, the greater number not

exceeding 8 or 10 acres and many not more than 3 or 4. It may be said about half

of the parish is let on old leasses at from 2 to 10 shillings per acre, and the

remainder tenants at will, averaging from 30 to 50 shillings per acre, for the

most part held directly from the landlord and paid wholly in money…”

“Soil

and Crops…Rotation of crops is first potatoes, next oats, barley. The soil is

rather light for the production of good wheat…”

“Occupations…Combined

with their agricultural employments …hand-spinning was the chief employment of

the women; but since the introduction of mill-spun yarn, it has become

altogether unprofitable.”

“Mills…There

are 8 mills in this parish…5 for preparing flax and 3 for grinding corn…With

the exception of the flax mill…(which is) on the River Bann, the streams which

turn the above (mills) have their source in or near the parish and are mostly

dry in the summer…The linen trade is not much followed here…Russell…(is)

the only manufacturer…”

According

to these surveys, about half of the 3,426 residents of the parish were

Protestant and half Catholic. There were 473 children in three open schools and

four smaller private schools, of which about 43% were female. Of the 323

students in the open schools, a quarter were Catholic. From these published

numbers it appears that out of a population of about 1,700 Catholic residents in

the Annaclone parish, only about 110 Catholic children were in the schools.

Based

on these surveys, the particular circumstances that existed in Annaclone in the

mid-1830’s certainly seem compelling if not perhaps overwhelming. It is also

important to consider that the British at this time held little sympathy or

regard for the Irish. It is probably fair to assume that the British bureaucrats

who undertook the surveys likely understated the circumstances which existed for

the Catholics of Annaclone.

From

these surveys, it is evident that agriculture was the primary means of

subsistence. However, all existing land was under cultivation. As no new land

was available for farming, the existing farm land required replenishment, but it

was completely uneconomical to move lime from its nearest source 12 miles away.

Almost

all farmers leased their lands from large landholders. It appears that as the

old leases expired, rents may have been jumping from 2 to 10 shillings per acre

to 30 to 40 shillings per acre. According to the 1930’s family history, John

was “a plow-man in Ireland (who) introduced lines, rope and then leather”.

John was also about 25 years old in 1837 and had either five or six younger

siblings. His parents, Tom and Mary, if they had their own farm, would have

likely leased between three and ten acres. This would hardly have been large

enough to support all five of their surviving children as they were now at or

approaching the age of starting their own families.

John,

being the oldest, may have even been under some pressure to find alternative

income to help support his parents and his younger siblings. More likely, he and

Bridget wanted to marry and start a family but there was no room in his family

home for a wife. His only option to marry Bridget may have been to start a new

life elsewhere. Hence, the longstanding family accounts that they left Ireland

on their wedding day.

Besides

their farming duties, the primary employment for women was hand-spinning. But

this had become “altogether unprofitable” with the introduction of mill-spun

yarn. According to the families histories, “Bridget sewed by hand for a tailor

in Pittsburgh”, and “In Ohio the women had wool pickings and apparently

prepared the wool for spinning. The women made all the clothes for the

family”. Also, Bridget’s father was “a farm-hand or a plow-man” in

Ireland, “who worked for the neighbors by the day”. Bridget “worked for a

rich man before she married”. Even though Bridget was clearly skilled at

hand-spinning, she was not spinning at the time she married John, but was

instead working for a rich man. Perhaps this was because spinning had become

unprofitable, and Bridget was then forced to find employment in another area,

possibly an area that had traditionally provided lower income.

The

source of fuel was mostly turf. However, the bogs in the Annaclone parish were

exhausted, including the 12-acre McClory’s bog. Most fuel had to be

transported from the adjoining parish.

Finally,

there was little opportunity for education, particularly if you were Roman

Catholic.

Perhaps

some of these factors set forth in the Royal Engineers’ surveys played a role

in John and Bridget’s decision to leave Annaclone, perhaps not. It is

interesting, however, to consider these factors in light of what we know of John

and Bridget from the family histories. They certainly appear to be consistent

and complimentary.

Distant

Irish Relatives

When

John and Bridget left Annaclone, they each left behind parents and siblings.

What became of our Irish ancestors, and whether any distant McClory relatives

can be traced in Ireland today have long been compelling questions. At this

point, some of the answers can be provided.

The

1930’s and the 1970’s histories by Mary Henneberry answered many of the

questions. Bridget’s had one sister who did not marry until about age forty,

and no mention was ever made that she had children. Her mother’s name was

Clark. There is some uncertainty as to whether her name was actually Dewey. Her

mother died young. Her father Peter lived as a bachelor for about 70 years and

died at about age 100. Bridget’s only sibling appears not to have continued a

family line. As a result, research would have to start with finding any siblings

of Bridget’s parents, who were probably born about 1790. This would obviously

be difficult and the chances for success slim.

John

had six siblings, two of which died young. His sister Nancy followed him to

Pittsburgh. A brother Henry came to Virginia, went west in 1854 and disappeared.

A brother Thomas moved to Liverpool, England where he owned seven pubs and had

four children. The final sibling, a brother Patrick, married Bridget Ward and

apparently had three sons – Pat, Ed and John Henry (presuming that the name

John Henry refers to one person and not two).

This

brother Patrick appears to be the only possible sibling who may have remained in

Ireland. As we knew the names of Patrick’s children, and given that Patrick

should have lived to about 1880, and his children to the early 1900’s, a

concerted effort was made to find a link. The Ulster Historical Foundation had

provided a long list of McClory gravestone inscriptions recorded from the two

registered Catholic cemeteries in the Annaclone parish. We visited and checked

every marker in these cemeteries plus an older, unregistered cemetery which

local residents directed us to at the corner of Churchill and Bluehill Roads

near the townland of Ballyshiel (which contained only one legible McClory

marker, which dated from the 1700’s). Over several days, we met with one

McClory and two McClory descendents, all from one large extended McClory family

in Annaclone. Although the meetings were one of the great highlights of the

trip, and the family resemblance’s notable, no definite connection could be

found.

John

McClory’s parents were Thomas McClory and Mary Morgan who were probably born

about 1785. There is no information as to the names of their parents or of any

siblings they may have had. No grave markers could be found for them. They

probably died between 1840 and 1870. Although there were several grave markers

going back to these dates and earlier, there certainly was not an abundance.

Many markers were also broken or so worn as to be completely illegible.

The

McClory and McClory descendents we met in Annaclone were wonderful, friendly

people. They were quite amazed that we had information on McClory's going back to

the 1780’s. They were also keenly interested to hear stories of the exploits

of McClory's who went to America. As to the Irish side of the McClory family,

they were not aware of any recorded histories and they had little information on

their family genealogies beyond their grandparents. Although we had information

on Patrick’s children who would have lived to the early 1900’s and who would

have started having their own children about 1870, they did not have, and were

not aware of, written information going back that far.

The

two registered Catholic cemeteries in Annaclone seemed filled with McClory

family grave plots, many these plots containing close to a dozen names. One of

the reasons we had come to Annaclone was in the hope of finding a connection to

distant McClory relatives in Ireland. We were expecting that our major

difficulty would be in finding enough information on McClory's. To the contrary,

the abundance of McClory information presented the real difficulty.

Unfortunately,

outside of the cemeteries, this no longer is the case today. The current number

of McClory's or McClory descendents remaining in Annaclone appears to be declining

quickly. According to Father Kearney of the Annaclone parish, there are only

three remaining families with the McClory name in the parish. Ireland is rapidly

becoming more modern and mobile. As has happened in America, children leave the

farms seeking opportunities in the cities. The parents remaining on the farms

pass on. To survive, the farms slowly get bigger and more mechanized, reducing

both the amount of labor and the number of farms.

In

conclusion, the best opportunity to establish a link to distant Irish relatives

was clearly through John’s brother Patrick. However, we have not yet been

successful in finding one. The real possibility also exists that Patrick left

the Annaclone area, or may have left Ireland.

The

1930’s and 1970’s family histories state that while John and Bridget lived

in Pittsburgh between 1838 and about 1851, many distant Irish cousins came to

Pittsburgh to visit cousins. The probable case is that we are somehow distantly

related to some, if not all, of the remaining McClory's of Annaclone, but most

likely at the level of John’s parents, Tom and Mary McClory, and the several

generations before them going back prior

to the mid-1700’s.

Tim

McClory of Oldsmar, Florida, a grandson of Leo, has set up a McClory Family

website at [http://www.mcclory.com/].

It includes links to other McClory websites where several family pictures and

memorabilia can be found. A copy of this report will

be posted there, with plans to also post some or all of the prior family

histories. Copies of this report will also be sent to our new McClory descendent

friends in Annaclone, including copies to Father Frank Kearney at the Annaclone parish for distribution to the three remaining McClory families in the Annaclone

parish. Hopefully, a wide distribution on both sides of the Atlantic may result

in the uncovering of new information or the encouragement of continued research.

I can be contacted in the Seattle area at (425) 313-7652; or by e-mail at [tgkearney@home.com,];

or by mail at 2216 – 271st Court S.E., Sammamish, WA 98075.

It has been many months since we visited Annaclone.

Research can go on forever and become all consuming. My wonderful wife Janet was

convinced months ago that this had already become the case. As usual, she is

probably right. At some point, it is also important to stop to summarize and

share the findings to date. Future findings can always be appended later.

Whether in America or Ireland, there may now or in the

future be a McClory descendent inspired to continue researching (and hopefully

correct any mistakes or undo any damage created by this self-anointed

researcher, for which I hereby apologize in advance). Since hindsight is often

twenty-twenty, it is easy at this point to have additional thoughts, after

thoughts, and after-after thoughts. In the event that they could be of help to a

future McClory family researcher, they are summarized below.